“On January 15, 1919, a two-million-gallon tsunami of molasses leveled Boston’s North end.

“Wait. Like, molasses … molasses?”

“Molasses.”

This is a common conversation I have when people discover I’m a historian. They often ask, “What’s your favorite crazy historical fact?”, and the Great Molasses Flood is a grade-A icebreaker. It is exactly what it sounds like. And that is, frankly, unbelievable.

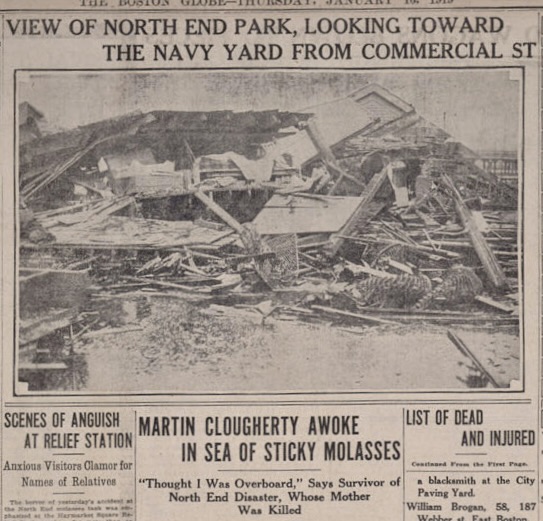

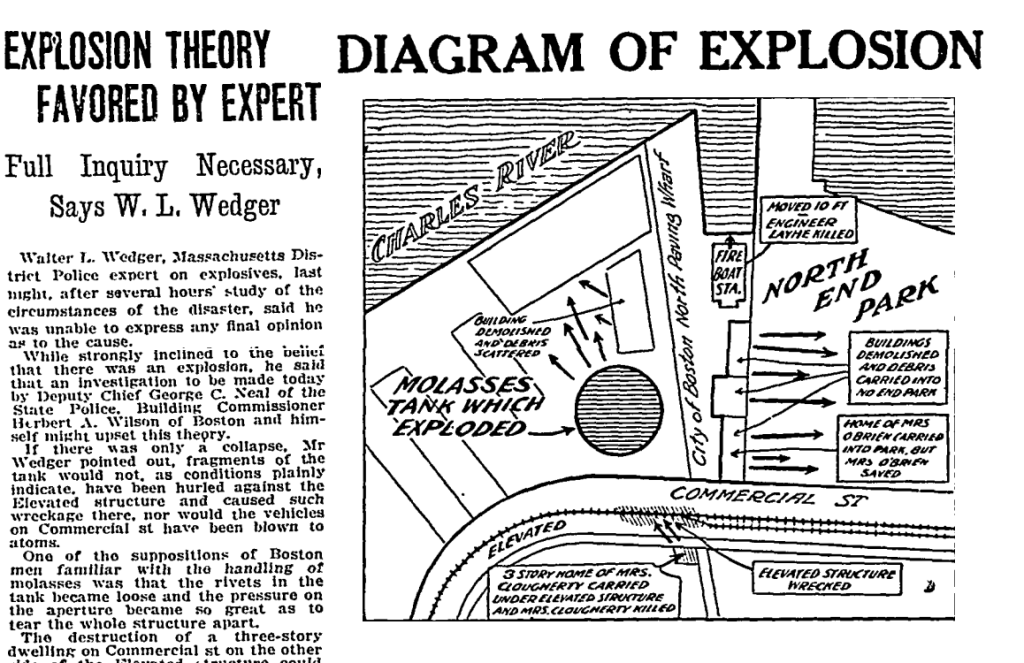

In a nutshell, a five story-sized tank of sickly sweet, sticky syrup burst and a fifteen foot “tidal wave of death and destruction stalked through North End Park and Commercial St”. I love telling this story because it is so bizarre. At face value, it sounds almost whimsical, or like an urban myth or an episode of The Simpsons. But, as soon as you start to consider it, the horror sinks in. Molasses is well known for being thick, sticky, and slow. But this wall of treacle careened down the street at 35mph. And because it is 1.5 times denser than water, it would have behaved more like a landslide than a flash flood. In the days after the disaster, the Boston Globe reported:

‘There was no escape from the wave. Caught, human being and animal alike could not flee. Running in it was impossible. Snared in its flood was to be stifled. Once it smeared a head – human or animal – there was no coughing off the sticky mass. To attempt to wipe it with hands was to make it worse. Most of those who died, died from suffocation. It plugged nostrils almost air-tight.’

Ultimately, 21 people were killed and more than 150 others were injured. Of those 21, about half of them literally drowned in the molasses. Including two ten-year-old children – Pasquale Iantosca and Maria Distasio who were returning home from school for lunch with Maria’s brother Antonio, who survived. Pasquale’s father watched from their apartment window as the children disappeared into the sludge. Others died in the following days due toinfection or trauma. More still were crushed under rubble. Most of the victims, including little Maria and Pasquale, were Italian immigrants – who made up 90percent of the North End’s residents by 1900 – impoverished by prejudice and circumstance.

I don’t tell this story merely because of its natural clickability. I think it’s an important case study on how we consider stories from the past. It feels other-worldly, and yet, placing it within its historical context sheds light on more than just the Molasses Flood of 1919.

How does something like this even happen? What was anybody doing with that much molasses in the first place? Beforethe First World War, molasses was the favorite sweetener in America, dating back to the first European colonies. Its strong flavor makes it perfect for spiced bakes (like those delicious little molasses cookies) and even more commonly, rum. But a 2.5-million-gallon tank seems a little excessive for household use. In fact, king molasses was already beginning to be usurped by granulated sugar for its dropping prices and longer shelf-life. So, we ask again, why did anyone need so much molasses? In a word, the Great War.

The tank was built by the U.S. Industrial Alcohol Company (USIA) which was in the business of fermenting molasses to produce ethanol, one of the key ingredients in gunpowder. So, even though the war had ended, the US being only a few votes away from prohibition (no more rum), and the availability of granulated sugar being on the rise, molasses was in surprisingly high demand in 1919. This demand, lack of federal regulation, and a culture of big business bolstered by the Great War and the Spanish Flu pandemic caused a fatal lack of oversight when it came to the construction of the USIA molasses tank in Boston.

It was 50 feet tall and 90 feet wide, capable of holding more than 3 million gallons of liquid. Although, I suppose ‘capable’, isn’t exactly the word. You see, the walls of the tank were less than an inch thick and the steel used had been mixed with too little manganese, making it devastatingly brittle in temperatures below 50 degrees Fahrenheit. A typical January day in Boston sits around 36° Fahrenheit (about 2° Celsius). After the flood, USIA claimed the rupture was caused by sabotage. They insisted that an exterior explosion was set up by an unknown individual as an act of terror against the company. The trouble, from their point of view, was that everybody already knew the tank was failing. Even before the fatal top-off in 1919, the tank had leaked. The leakage was so significant and well-known that kids and grown-ups alike would grab a free cup like it was a sugar fountain. The company responded by recalking some of the biggest cracks and painting the whole thing brown so you couldn’t see the sweet stuff seeping down the sides. Eventually, an employee of the company presented hunks of metal to the USIA executives as evidence of the danger to which they reportedly replied, “The tank still stands …” Given all this evidence, the residents of the North End filed suit and litigation lasting more than five years ensued. In the end, it was determined that the tank was structurally unsound, external forces did not cause the disaster, and USIA was liable for negligence. Ultimately, USIA paid more than $600,000 (the equivalent of more than $10.5 million today) in settlements. The victim’s families received $7,000 each. This was the first successful class action lawsuit in the United States.

But beyond this being a bizarrestory, what’s the point of telling it? Well, this disaster served as a springboard for modern regulation and oversight and serves as a great case study for the need for corporate and industrial ethics. But the most important reason to tell this story is that despite it being such a fantastical event, almost no one I talk to has heard of it. Much of the period from 1900 to1919 is strangely vacant from public memory in the US. Author Stephen Puelo argues that the flood may have fallen out of memory because no one of social significance was affected. The property damage – besides USIA’s – was largely city and working-class residences and businesses.

Today, the North End is considered Boston’s “Little Italy.” With its saint festivals and divine cuisine with cannoli for days, it is one of the highlights of tourism in the city. It is also Boston’s oldest neighborhood. Before the Revolution, its proximity to the harbour provided a perfect place to settle and build a shipping empire. The population boomed, factories and industry moved in, and the poor immigrant residents did not move out. By the mid-19th century, the North End became one of the country’s first tenement slums. As the Irish community began to assimilate into social acceptance, the Italian immigrants were ruthlessly criminalized by American society. They only had each other, and the North End became a powerful community of (mostly) Southern Italians. The single square mile neighborhood was extremely overcrowded and covered in soot and grime, but it was the one place they could find housing and safety in numbers. However, most of the Italians of the North End were apolitical non-citizens and therefore had little power to speak out about injustices being imposed on them by big business and the state – like the recklessly swift construction of a three-million-gallon molasses tank right outside their front doors. This likely was a major factor in USIA’s selection of the site. Proximity to the harbor, to be sure, but also the fact that no one was going to speak for the safety of these people until it was too late.

Another reason the flood has essentially disappeared from public memory is that there were so many other watershed events going on in the world at the time. The Great War had ended two months before, the 19th amendment was nearing ratification, Prohibition was knocking at the door, and the Spanish Flu pandemic was raging through the nation. The Roaring 20s are considered a time of major social change in the US and the causes of that change were eclipsed by the political, cultural, and economic upheaval seen in the following years. So, while the smell of molasses lingered in the streets of Boston for decades, it too eventually faded.

Further Reading:

Stephen Puleo, Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 (Boston, Mass: Beacon Press, 2004).

Jessica Wadley is a student on the MA in Public History programme at Royal Holloway, University of London.