History matters. Our histories warn us, inform us, and inspire us. More than that, they help us know ourselves, and shape what we believe we know about each other. As I was getting ready to go to the first protest outside the newly-unveiled Ripper Museum in Shadwell, I started looking for a quote which could express what I was struggling to say. The quote I found was from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s excellent TED Talk about the ‘single story’ of Africa:

The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.

The infamous Whitechapel Murders have long overshadowed the many stories we could tell about east London, and the obsession with ‘Jack’ means that the story most people associate with the area is one of violence against women and failed justice. Yet if our single story is about the brutal, unsolved murders of five working class women, how does that shape the way people see us? How does it shape the way we see ourselves?

#StufftheRipper

The Ripper Museum has offered plenty of reasons to be angry: not least the mythologising of a misogynist serial killer, and the insult of swapping a museum presented to the local community and council as about women’s lives for a tourist attraction about their violent deaths – complete with a mannequin of one of his victim’s corpses, ‘Ripper’ cupcakes, and an audio loop of women’s screams.

The museum is, however, just the latest and most egregious example of London’s Ripper tourist trade (although the London Dungeon seems to be challenging them for the crown). And yet contrary to the narrative presented by many of the institutions and individuals involved in this ‘trade’, violence against women hasn’t gone the way of gaslights and top hats. It is incredibly common and frequently lethal, and Ripper tourism helps to trivialise it. The story is told again and again with no reference to the wider context of violence against women – especially violence against women sex workers – and usually in an insensitive, sensational, titillating way.

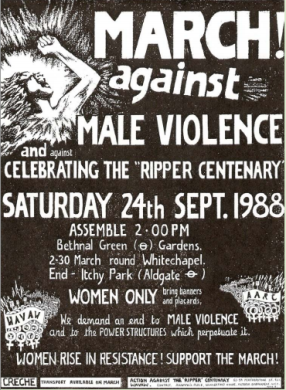

The protest at the Ripper Museum in 2015 wasn’t the first such protest by a long stretch. One of the local historians who has inspired me most, my co-author Rosemary Taylor, recalled a women’s march that took place 25 odd years ago in protest at the Ten Bells pub which had essentially reinvented itself as a Ripper theme pub, with t-shirts for sale behind the bar. More recently, the Women’s Library (when it was based in Aldgate) and the LIFT campaign both ran Alternative Ripper Tours which told the stories of the women who were murdered – their lives, their communities – and put up temporary plaques to honour them. Protests have also been staged online, including one by the Everyday Whorephobia blogging collective, which ran an online campaign condemning Ripper tourism in 2013.

Feminism is cool now?

One of the things that has set the ‘museum’ on Cable Street apart, attracting criticism from so many sources, is their baffling attempt to pass off the attraction as a genuine celebration of women’s history – even after the logo of a top-hatted man standing in a pool of blood was revealed, and the contents of the museum exposed. It was a bizarre strategy, which they thankfully now seem to have abandoned. It was particularly eerie for us to see the language we were using to describe our fledgling East End Women’s Museum co-opted for their press releases. Indeed, it’s interesting that the Ripper Museum’s owners felt that a museum of women’s history would be more likely to receive interest and support than a museum about Jack the Ripper, a longstanding staple of London tourism. On the one hand this is a testament to the strength of the current resurgence of feminist activism, and to decades of work by pioneering women’s historians. On the other, it reveals the extent to which a particular aspect of feminism has become depoliticised and absorbed into the mainstream. Perhaps the Ripper Museum is an extreme example of ‘femvertising‘. Much has been written about the oil industry’s support for museums, and the ‘halo effect’ they hope to glean from sponsoring exhibitions – could it be that the Ripper tourist industry was seeking out the same respectability?

Missing women

At primary and secondary school level the history curriculum is not particularly concerned with women’s experiences. A recent survey by Girlguiding UK revealed that over half of girls aged 11-21 say that the role women have played in history is not represented as much as the role of men. In higher education women’s history is typically something to be sought out proactively, as an ‘added extra’ or specialism. Yet the problem is by no means confined to our classrooms; women are underrepresented on a local and national level in public history, in museum collections, archives, and academia. Just 2.7% of UK public statues feature historical women who weren’t royalty, with only one statue of a named black woman in the entire country. Just 13% of English Heritage blue plaques in London honour women and only four of the 50 bestselling history books in 2015 were written by women. Unsurprisingly, where women do appear they tend to be those with the most privilege, with women at the intersections of oppression rendered almost invisible. The histories of women of colour, women with disabilities, lesbian and bi women, trans women, and working class women have not only been pushed to the margins but right off the page.

History for resistance

Why does this matter? Unsurprisingly, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie said it better than I can, in the same TED Talk:

Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity.

Marginalised histories can be powerful tools to dismantle stereotypes and counter myths, to challenge assertions that ‘this is how it’s always been’. Sometimes a story can get through where an argument can’t. Uncovering hidden histories can also play a part in consciousness-raising. Recognising shared experiences across decades, even centuries, help to make the deep roots of inequality and structures of power visible. It means something to discover that your struggle is not only individual but shared, not accidental but systemic. That’s not to suggest that there is a single shared female experience or history, but simply that there are many common threads. Besides, examining the differences between women’s experiences is as illuminating as looking for similarities. We mustn’t simply replace Top Ten Kings and Generals with the Ten Best Ladies, but rather widen the lens, enlarge the story, and examine the power structures which cut across women’s history too.

Something else women’s history can offer us today is inspiration. Studies suggest that women and girls respond better to role models who are also women and girls, and there is something especially magic about a local hero. (I’m writing this in a cafe in Stratford less than 100m from a statue of my most local hero, Joan Littlewood.)

The East End Women’s Museum

While we hope that the lessons we learn through the East End Women’s Museum may be useful to women’s history projects elsewhere, our focus is firmly on east London. Although we do use a deliberately loose and ahistorical definition of the area, rather like John Strype in 1720 when he described the district as “that part beyond the Tower”.

Our reasons are practical – this is a big enough job as it is! – but also because east London has incredibly rich social, political, and cultural histories, and will allow us to explore many themes which are supremely relevant today, such as housing, migration, poverty, and dissent. Besides, it’s overflowing with brilliant stories of pride, pleasure, creativity, humour, resilience, resourcefulness and of course, resistance – from the Bow Matchwomen’s Strike to the Battle of Cable Street, the Ford Dagenham machinists’ walkout to the Bengali families squatting empty buildings in Spitalfields.

Challenges ahead

We’ve been very lucky to have had such a lot of goodwill and enthusiasm for our project, but there are some challenges ahead. One of the most pressing is lack of funds. We’ve reached a point where we can’t expand the project until we have funding to cover things like volunteer expenses, travel, and printing costs. Aside from practical challenges, there are other issues to contend with: for example, as our profile grows we are encountering more criticism and hostility. We’re more often reminded that some people feel very threatened by the idea of throwing a spotlight on women’s history, as if by including more stories about women everyone will suddenly forget about Henry VIII, Newton, and Brunel. While it’s frustrating and sometimes unpleasant, the backlash tells us that we’re on the right track.

What we hope to achieve and how

Our goal is to research, record, and represent women’s histories from across east London, and in doing so celebrate a shared local history, challenge gender stereotypes, and offer inspiration. We want to create opportunities for women and girls to gain the skills and confidence to tell their own stories.

Our hope is that we can build a long lasting resource for historians, schools, curators, and community groups. We know that many museums have slender resources and little support to diversify their collections, especially as past decisions about what is ‘important’ influence what is available to us today. We want to partner with more fantastic archives, collections, and community heritage projects and work together to get the girls to the front. We’re drawing on approaches including oral history, family history, social history and narrative history. Our ultimate aim is to co-create the content of the museum with groups from across east London, and to make it as accessible as possible, collecting and sharing stories in public spaces – parks, streets, schools, pubs, places of worship – as well as in our own museum space and online.

We’ve already started doing a lot of this, thanks to the support of some fantastic partners and volunteers. Over last year we’ve helped to develop two joint exhibitions – with Eastside Community Heritage and the East End Women’s Collective – and begun working on a third with Hackney Museum. We’ve also staged a sell out history event for local feminist activists, organised a pilot schools workshop with 70 year seven students in Hackney, and launched a research project that explores the history of women and East End markets with University College London and King’s College London. This year our main focus is putting some firm foundations in place while we continue to listen and learn about what would make the best possible museum for the women and girls we aim to serve.

An East End mystery

Returning to the idea of the ‘single story’ of east London, I often hear that what makes the myth of Jack the Ripper so irresistible is the element of mystery. I don’t doubt that’s the case. But here’s another mystery for you: why aren’t the other stories better known? Who does it serve to sideline women’s voices and experiences? Or to present working class people as powerless, to suggest trans identities are just a recent ‘trend’, to portray sex workers only as helpless victims, or to paint a picture of London in which every face is white?

Sarah Jackson is co-founder of the East End Women’s Museum and author, with Rosemary Taylor, of East London Suffragettes: Voices from History.

I agree with so much of this. But it’s far too polite. The obsession with the Ripper story (are the relevant files still the most requested items in the NA/PRO?) is pornography, very violent pornography hiding behind the respectable masks of local history and “unsolved mysteries”. I read this blog after seeing for the first time on TV a rape story which was not presented in a prurient, voyeuristic fashion (Broadchurch) but with sensitivity about a woman’s pain and trauma. The Ripper obsession should be denounced for what it is and the recording and presentation of the history of women celebrated as a much needed corrective.

LikeLiked by 1 person