We welcome the useful contribution made by Historians for Britain in the current issue of History Today, which provides a timely reminder of the value of history in contemporary debate. More specifically, it raises important questions about British nationalism and claims of Anglo-exceptionalism at a significant moment in time for both. As historians, however, we take issue with the statement’s highly reductive distortion of the history of the United Kingdom.

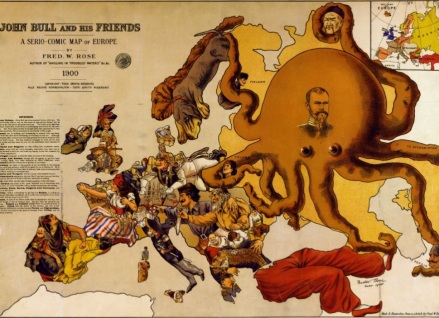

The authors seem to have interpreted the past to fit their desire to see a renegotiation of Britain’s EU membership in the present. And while they don’t even hint at what aspects of British membership they would like to see renegotiated, they clearly feel that the country’s ‘largely uninterrupted history since the Middle Ages’ sets Britain apart from her continental neighbours. The unambiguous proposition is that as national communities from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean struggled through a millennium of violent discord and political discontinuity, Britain followed its own relatively stable, more enlightened special path. This argument doesn’t stand up to even the most casual scrutiny.

As evidence of Britain’s unique historical trajectory, the authors cite ‘principles of political conduct that date back to the 13th Century’. This is presumably a reference to the notions of liberty for all that are thought to have been enshrined in the Magna Carta, sealed by King John in 1215. Yet although this medieval treaty between the Plantagenet king and his feudal lords was later interpreted in an admirably liberal fashion by some, its originally intended purpose was anything but democratic. In terms of ancient systems of democracy, Greece clearly has a much stronger claim than Britain, and the UK was behind several of its continental neighbours, including the Netherlands, Germany, Poland and Denmark, in introducing modern universal suffrage. A genuinely democratic system of government was fiercely resisted by political and social elites in Britain and had to be fought for, tooth and nail, until it finally arrived in the late 1920s. Those who continued to be subjected to British imperial rule would have to wait longer.

The authors are also on shaky ground when they allude to long-standing institutions such as the ‘British’ monarchy and ‘several universities’ that have ‘survived (and evolved) with scarcely a break over many centuries’. To begin with, given that the Plantagenet monarchy was born as a result of Norman invasion, and that most of the its kings were French and ruled over large parts of France, and that William III was Dutch and George I and George II hailed from the German lands, the monarchy arguably represents the historical European influence in British life more than any other domestic institution. Indeed the late Queen mother was the first British-born spouse of a British monarch for over 200 years. More importantly, however, the monarchy is hardly a continuum and the toppling of British ruling dynasties has often been extremely bloody. The dynastic Wars of the Roses of the 15th century, fought over competing claims to the English throne, had a traumatic impact on English communities. In an even more violent chain of events, the Stewart monarchy was toppled by two bitter civil wars that culminated in the execution of Charles I and the establishment of the Commonwealth with Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector in 1649. The claim ‘that the British political temper has been milder than that in the larger European countries’, dubious in the context of the 19th and 20th centuries, is downright spurious with reference to the 17th century.

The cosmopolitan and often distinctly European character of successive British monarchies is arguably matched by the international outlook of Britain’s more ancient seats of learning at Oxford, Cambridge, St. Andrews and Glasgow. All of which, crucially, have a great deal in common with their counterparts in Bologna (founded in 1088) Salamanca (founded in 1134), Prague (founded in 1348), Heidelberg (founded in 1386) and a host of other long-standing European institutions. And as any historian of ideas can confirm, the intellectual elites in the countries that now make up the EU have been corresponding, collaborating and falling out with each other for centuries.

On a somewhat more negative note, and as Neil Gregor has pointed out, the historical experiences that arguably bind western European states closest together are colonial conquest and imperial expansion. Yet perhaps the most misleading aspect of the ‘Historians for Britain’ statement is the authors’ refusal to come out and say exactly which state or nation or country they’re actually discussing when they refer to ‘Britain’. In a howler that is not only bad history but bad geography to boot, they maintain that ‘even Britain has contracted, with the departure of most of Ireland.’ At the risk of stating the obvious, Ireland has never been part of Britain. The island was under some form of ‘British’ rule from the end of the 12th century until well into the modern period, it formed part of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ireland) from 1800 to 1922, and Northern Ireland of course remains within the UK. In Britain itself, there are three distinct nations, each of which has colourful layers of internal complexity influenced by class, region, ethnicity and religious outlook. The cultural and social landscapes of England, Scotland, and Wales have also been greatly enriched in the past two centuries by the influx of immigrants from across the globe, including continental Europe. If the authors of the statement are genuine in their desire to inform the public about the history of the UK, they should be prepared to acknowledge this. Yet it is this very refusal to recognise conspicuous historical diversity within the British state that suggests that ‘Historians for Britain’ are not really interested in the complexity of Britain’s historical relationship with continental Europe. What they are interested in is a Eurosceptic political agenda. They are perfectly entitled to this, but, as historians, we call for a sincere, open debate based on an informed, evidence-driven discussion of the past.

We believe that historians have a potentially valuable role to play in communicating with the public about the past and we warmly welcome comments or contributions from anyone who would like to weigh in on the debate.

Edward Madigan, Lecturer in Public History, Royal Holloway, University of London

Graham Smith, Senior Lecturer in Oral History, Royal Holloway, University of London

__________________________________________________________________

This statement is also supported by:

Sarah Ansari, Professor of South Asian History, RHUL

Angela Bartie, Lecturer in Scottish History, University of Edinburgh

Justin Champion, Professor of the History of Early Modern Ideas, RHUL

Markus Daechsel, Senior Lecturer in Modern Islamic History, RHUL

Helen Graham, Professor of Spanish History, RHUL

Jonathan Harris, Professor of the History of Byzantium, RHUL

Zoë Laidlaw, Reader in British and Imperial History, RHUL

Andrea Mammone, Lecturer in Modern European History, RHUL

Rudolf Muhs, Senior Lecturer in European History, RHUL

Andrew Perchard, Senior Research Fellow, Coventry University

Robert Priest, Lecturer in Modern European History, RHUL

Dan Stone, Professor of Modern History, RHUL

Björn Weiler, Professor in Department of History & Welsh History, Aberystwyth University

Anna Whitelock, Director of Centre for Public History, RHUL

[…] 17 May: Historian for History Statement May 2015 […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on ReThinking the City.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A thought provoking response to an article clearly hindered by British branded blinkers

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] apart from the rest of Europe. Since its publication, it has kicked up a storm of reactions, with historians at Royal Holloway and the History Vault as well as Neil Gregor, Neville Morley and Charles West at History Matters, […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] established this blog in response to ‘Historians for Britain’ (see our opening statement) and to provide a forum for historians – and anyone with an interest in history – to join the […]

LikeLike

[…] for a little Britain based on the old chestnut of British exceptionalism has been countered by the Historians for History, who insist that history should not be used for political propaganda and ‘take issue with the […]

LikeLike

You say 1215, I say 1216 – so much for “no divisive invasion since 1066”. Abulafia’s piece is utter charlatanry that should offend even an honest eurosceptic. These people call themselves historians? If only we still had Corfu, all would be well? Count me in.

LikeLike